Correspondence with

Ansuya Blom

Hendrik FolkertsIn: Metropolis M, no. 4 (August/September 2020)

Chicago, 16th May 2020

Dear Ansuya,

What a great privilege to get to know your work again. There were moments of recognition and new encounters — your oeuvre is like a large room filled with old acquaintances and future friends. At the same time, I realized that our conversation wouldn’t be a regular ‘interview’. Your work requires a different approach.

Writing this letter is the closest I can get to touch. My hand encircles the pen. There is the interplay of muscles, tendons, nerves and bone, driven by impulses shaped by memory and desire. Let’s talk about ‘touch’ (a rather controversial notion these days) and closeness. The intimacy of the sign, but also of the systems that, consciously or subconsciously, order and determine this for us, whether these are the conventions of language and communication or the limitations of the material.

You wrote in your book Touch on a hard surface (2009), 'For me drawing is touch on a hard surface.' ('Drawing is thinking through resistance, however light this resistance might be.') Has your relationship to paper changed over the years? How does this resistance translate to other materials and surfaces in your work?

A little later, you wrote, 'I find myself drawn to those who do not concealbut reveal.' You speak of the ‘poetic capacities of immediacy’. In many of your drawings, there is a specific relationship between revealing and concealing (or rather in making unattainability visible) — what we see and what remains hidden. Where does the desire to reveal come from? What drives it? What appeals to you in that immediacy? And what remains hidden?

These times question both the form and content of things, and we can start dreaming again. To quote the title of a work from 1989: 'In dreams begin responsibilities'. What will your answer be? Will you write me a letter back?

Looking forward to our correspondence!

Hendrik

Dear Ansuya,

What a great privilege to get to know your work again. There were moments of recognition and new encounters — your oeuvre is like a large room filled with old acquaintances and future friends. At the same time, I realized that our conversation wouldn’t be a regular ‘interview’. Your work requires a different approach.

Writing this letter is the closest I can get to touch. My hand encircles the pen. There is the interplay of muscles, tendons, nerves and bone, driven by impulses shaped by memory and desire. Let’s talk about ‘touch’ (a rather controversial notion these days) and closeness. The intimacy of the sign, but also of the systems that, consciously or subconsciously, order and determine this for us, whether these are the conventions of language and communication or the limitations of the material.

You wrote in your book Touch on a hard surface (2009), 'For me drawing is touch on a hard surface.' ('Drawing is thinking through resistance, however light this resistance might be.') Has your relationship to paper changed over the years? How does this resistance translate to other materials and surfaces in your work?

A little later, you wrote, 'I find myself drawn to those who do not concealbut reveal.' You speak of the ‘poetic capacities of immediacy’. In many of your drawings, there is a specific relationship between revealing and concealing (or rather in making unattainability visible) — what we see and what remains hidden. Where does the desire to reveal come from? What drives it? What appeals to you in that immediacy? And what remains hidden?

These times question both the form and content of things, and we can start dreaming again. To quote the title of a work from 1989: 'In dreams begin responsibilities'. What will your answer be? Will you write me a letter back?

Looking forward to our correspondence!

Hendrik

Amsterdam, 22nd May 2020

Dear Hendrik,

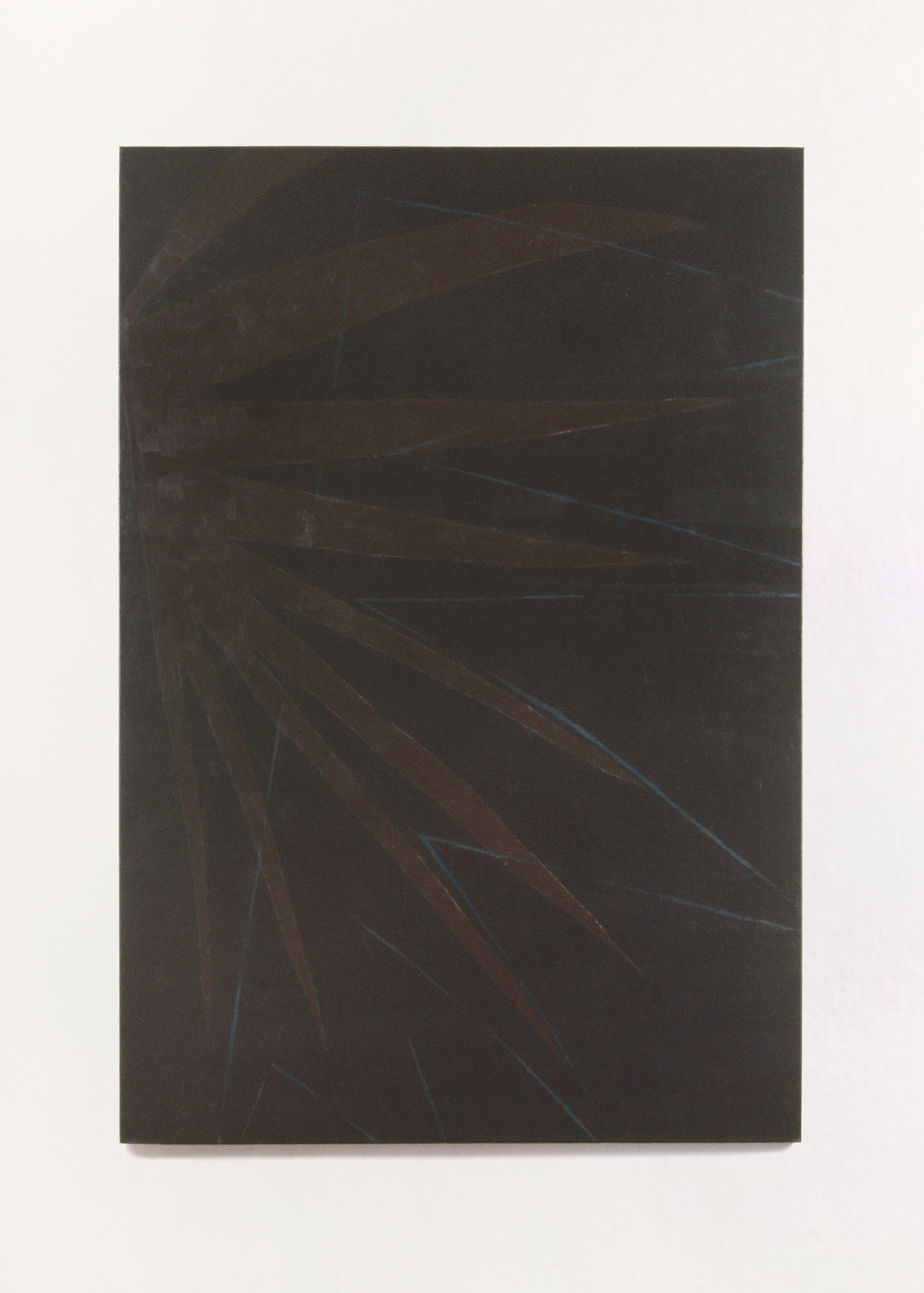

One of my first memories as a baby is of seeing my own hand. In 1982, I read Bayamus (1978) by Stefan Themerson, a Polish writer and visual artist who was important to me at the time. After reading your letter, I opened the book again. It fell open on the sentence, ‘And suppose your finger is an artist.' In 1979, I had made a number of black paintings, Kwanza, which were important to me though I couldn’t exactly say why at the time. Working in black on black gave me oxygen and I know I was very emotionally involved in them. They were paintings of large abstracted leaves. But others saw these paintings as pure formal expression, for me it was a schizophrenic situation that I couldn’t make sense of.

Around 1982, I started becoming increasingly bothered by the wobbly linen of stretched canvases. I couldn’t do it anymore, the distance from brush to image had become too great, not helped by the fact that the canvas seemed to float in the air. Instead of linen, I started working on paper that I pinned to the wall, I started drawing more and my work became more physical.

The resistance of the wall was not oppressive but rather expansive. The physical distance from my hand to my work was no more than the length of a crayon or pencil. I was looking for a reality that I recognized and that spoke to me and it felt as if the image was in the paper instead of me putting something on it.

Over the years, the relationship between drawing and writing has become more important and I try to link my choice of materials to that. Touching the material as an extension of my thoughts remains a necessity. In 2008, I wrote in Letter to J., 'drawing is touch on a hard surface. The element of resistance is embedded: paper is supported on a hard desk, or on a solid wall. Drawing is thinking through resistance, however light this resistance might be.' For me, it was a form of resistance.

You write about the collective consensus through use of signs. The collective also instils a fear in me. It’s not so much the signs that can seem limiting but mainly the way that the language they form is interpreted. Which brings me to your second question, which I understand as a question about mental touch that is nonetheless direct.

I am very moved by ‘naked’ texts, without armour, where the language doesn’t symbolically conceal despair or fear but rather describes it physically so that it becomes material. The poetic capacity is located in the inescapability of the words and in such a way that a mental state is palpable. The search for footing, the unstable balance, has so much value precisely because of its humanity. I love language whose words touch me like fingers.

For a long time, I have been apprehensive of the way society likes to exclude everything different. In the common sense thinking of what is ‘reasonable’, ‘not too many’, ‘not out of control’, there is no place for people whose suffering is too open and exposed. The idea of the abject fascinates me. At what point is someone or a group labelled a despicable entity and what happens in the perception of others? More and more, I see my work as an attempt at ‘sense-making’, an attempt to understand the incomprehensible.

I loved what you wrote about ‘making the unattainable visible’, I recognize myself in that. In my work, I want to show that I take away and add, it’s a kind of push and pull. It is sometimes a revisionist action, where I can take away what is judgmental and frightens me, or add what I long for. It is also a kind of incantation. The incomplete and fragmentary is dear to me because it doesn’t offer the illusion of an intelligible world. It is an attempt to get as close as possible to an internal experience, even if it is probably never fully legible to another person.

Ansuya

Kwanza I, 1979, oilpaint on canvas, 185 x 127 cm

Chicago, 25th May 2020

Dear Ansuya,

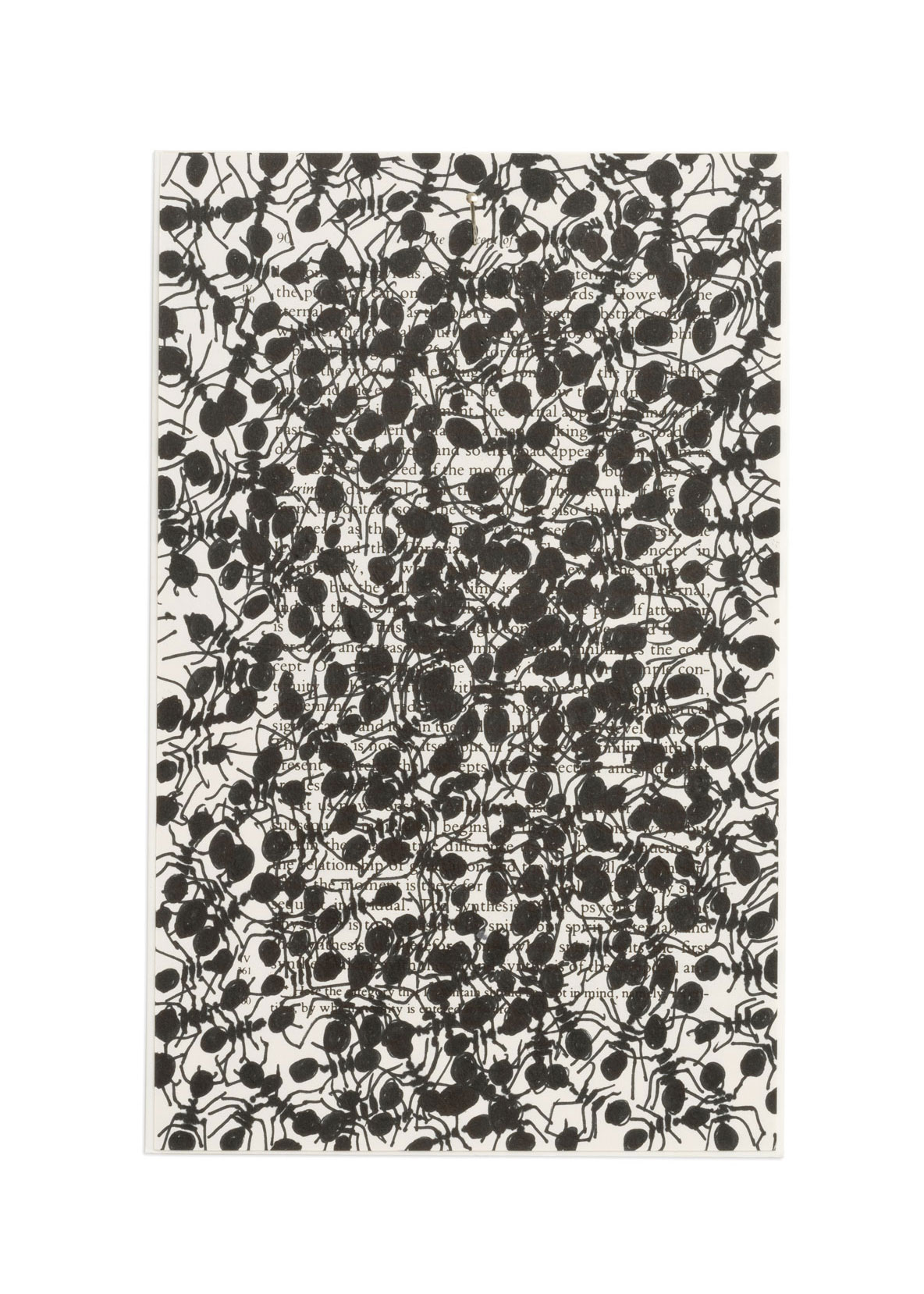

Your last paragraph, but also how you describe ‘naked texts’ that derive their power from the inescapability of words, brings me to language, and how the spoken and written word manifests itself in so many different ways in your work. For example, your own poetry, as in the short film Ysabel’s Table Dance (1987), where the words from your 1986 poem of the same name stand alone, as well as in relation to the image and movement (as spoken text). In your films and drawings, quotations play an important role. In your art book War Songs (1984), you use texts by writers James Baldwin and Langston Hughes; the words of comedian and writer Richard Pryor and Native-American poetry appear in your film Hither come down on me (2007); in the series The Concept of Anxiety (2007-2008), we find pages from philosopher Søren Kierkegaard’s book of the same name (covered in drawn lines and ants); and you transcribed texts by the writer Robert Walser onto shapes that resemble traces or stains on the film negative in The Walk I-VII.

How did language originally gain a place in your work? What does the word do in relation to the image, be it a moving image in film or a drawing? How would you describe the use of other authors’ texts? Do they function for you as quotation, a form of (visual and conceptual) intertextuality, or (and I lapse somewhat into interpretation here) another surface, which, like the paper or the wall, offers positive resistance?

Hendrik

Amsterdam, 26th May 2020

Dear Hendrik,

Your comments and questions make me think. I was in New York regularly in the early 1980s. The art scene there was refreshing and contrasted with the formal approach of the Dutch art world. It fed my need to be more explicit about shaking off abstraction, and in 1983 I decided to make a short film based on Sylvia Plath’s Lady Lazarus. Her poem touched me because of its direct language, its openness and its subject matter; it broke the taboo of talking about suicide.

In Ysabel’s Table Dance, I wrote out of a desire to challenge and invoke a reality. But, after a few films, because I wrote my own texts and in the first person, I started to find it suffocating that autobiographical links were immediately made. To create some distance, I started incorporating the words of others. The point was the position of the first person singular, which I also recognized in other writers. ‘I’ as a position.

In my first films, I used text as a complete ‘story’, with the images running more or less parallel to it. Along the way, the directly accessible language faded into the background and a mental state emerged. The focus was not only on language itself, the presence of voice and sound also played a major role. In the fragmented texts, the gaps that fall between sentences are as important as what is said. There is an incompleteness that is dear to me.

Language is both meaning and image. My relationship to other people’s texts is absolutely affective, and almost always comes from being moved. I am interested in those who are trapped in language, the ‘objects’ of judgement expressed by the structured language of others. The quotations I use are evocative to me, they are material whose origins I want to show, making those behind the text also partly present, where different realities literally coexist and overlap. And I am aware that, like a kind of butcher, I chop, slice and bring together so that the words together express a certain state of being.

How wonderful you suggested the analogy that a quote offers a positive kind of resistance. This resistance works for me as a kind of trampoline from which my thoughts can bounce and land in another space. I like analogies because, between the parallel lines that are then created, there is room for other meanings and realities that don’t have to fit entirely. Polyphony is beautiful in the simultaneity of the many.

To me, Richard Pryor is the personification of the subjects of his stand-up shows and he eludes categorization. Besides a text of his, I also used the sound of his voice in a film about fear, because that sound was so expressive and telling. His jokes about racism expose truths that go beyond the joke and are so special in all their extremity. I’m writing to you against the backdrop of the murder of George Floyd in your temporary (?) country and wonder what Richard Pryor would have said …

I’ve used different kinds of texts in my work. The letter and the diary, written without being intended to be published, are perhaps the closest to an internal truth for me because of the tremendous intimacy and the realization that no or only one pair of eyes will fall on the paper. Would I write to you differently if I knew you were the only reader of this letter, and if so, what?

Ansuya

P.S. 1

You wrote that now is a time for poetry and I thought of the resistanceof the wall. The other space that opens up through that resistance might be poeticspace, one can’t possibly say for sure where it is. For now, poetic space for me isa space where a not-knowing can exist and this not-knowing offers an openingthrough which other forms of insight can emerge.

P.S. 2

Following your comment on intertextuality, I thought of ‘my writers’,the ones with whose work I have a long-standing relationship. That relationshipis not necessarily born of a critical analytical attitude towards their texts butof a love for them. R.D. Laing put it so beautifully, ‘Words are simply the finger pointing to the moon.’

The secret life IV, 1999, coloured pencil on burnt paper, 230.5 x 150 cm

Chicago, 2nd June 2020

Dear Ansuya,

The murder of George Floyd, the countless murders that preceded his death, the looting, the police brutality, the constant flow of news and media,the possibility of military intervention, and the prospect of the election possibly being won once more by a neo-fascist, sadden me immensely, while the peaceful demonstrations and the incredible strength that lies in this protest energize me to keep fighting, offer support to people who need it most, and make a difference in my work and relationships. I’m sharing this with you because, consciously or subconsciously, it will affect the continuation of our correspondence.

I’d like to talk to you some more about the first person singular: '"I" is not me, it is a position.' as you write. This brings me on to psychoanalysis. You have a master’s degree in this field, you use the transcripts of historical conversations between psychiatrist and patient in some of your works, and your work constantly explores the limits of subjectivity.

How do notions like ‘alien’ and ‘familiar’ relate to each other in your work, and in particular to the chosen position of the first person singular? Is this position possible, or is it a multiplication of positions within a body (I am thinking of your work Nowhere else (1991) as well as Jean-Luc Nancy’s 1996 book Being Singular Plural)? Was there initially a certain reciprocity between your art practice and your interest in psychoanalysis? And how has this changed over the years?

I’m enjoying your responses. They currently point to a half-moon over Chicago. The city is quiet for now.

Hendrik

Amsterdam, 7th June 2020

Dear Hendrik,

The relentlessness of the killing evokes other moments of physical and linguistic violence, and the fear that nothing will change in the end. But like you, the images of protesters and police officers taking the knee move me. Each time I hope that the still-unrelenting loud protests will bring us just one step closer.

For me, the first person singular is the domain of existential solitude. It is a position in which the internal experience implicitly entails loneliness, not only because of the uniqueness of the experience, but also because it is difficult to convey. The beauty of the word ‘singular’ is the duality of meaning, the fact it describes both the solo position and the unique position. But at the same time, there is a universality in it; everyone essentially knows this position, or rather, this condition. Perhaps the gap of solitude becomes less deep thanks to recognition in and of another, and a first person plural emerges.

Alienation is something that fascinates me but it is not so easy to describe. ‘Alien’ includes the outsider who is not recognized or acknowledged. The unfathomability, the black hole, that this creates instils anxiety, as Kierkegaard writes: ‘Nothingnesss constitutes anxiety.’ ‘Alien’ is the moment a person no longer recognizes himself in a mirror held up before him. But while I see that the common or shared is important, I also recoil from the assumption of a ‘we’ if its condition is not clearly stated.

For me, psychoanalysis is a frame of mind where attempts are made to get to the bottom of the contradictions that reside within people, where questions are raised about what is known or understood, and eyebrows are raised about the dominance of the measurable. I haven’t worked directly with psychoanalytic concepts in my work, and in this sense there is not so much reciprocity.

My relationship to psychoanalysis has certainly changed over the years. Gradually, I became troubled by the way certain concepts were approached but also by the emphasis on the symbolic function of language. It became perhaps too self-conscious and lacked life for me. I became more interested in the unnameable, the ‘real’ and its far-reaching influence. Édouard Glissant brilliantly formulatesthe following: that which is not accessible is not dangerous, and we don’t need to worry about not being transparent to each other. It is precisely that tolerance for each other’s opacity that prevents barbarism.

I’m aware that time is running out and this may be my last letter. Making explicit something that is also partly intuited makes my jaws seem to want to clamp while, in an attempt to be concise yet complete, my hand continues to string the words together. Since the quote played a part in our exchange, I cannot help but salute and thank you with the words of Lola V. from 1930:

With warm wishes … yours truly … devoted

Ansuya

The Concept of Anxiety, 2007/2008

Detail

Detail